- Home

- Jessie Close

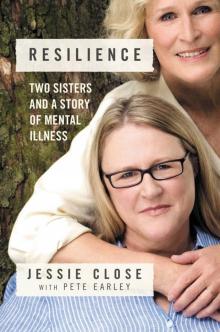

Resilience Page 4

Resilience Read online

Page 4

Knowing Sandy was next door made me feel less afraid, but I still wished that he was in the bed next to mine. I felt totally alone.

Finally, I fell asleep.

VIGNETTE NUMBER ONE

by Glenn Close

It’s strange how memory can distill something down to a single image and yet somehow that single image retains its power to invoke all the other senses. I realize now that my memory of my little sister, Jessie, when she was a child is a collection of images around which other sensations move in and out of my consciousness. Maybe that’s because, compared to most other families, our family has a shocking lack of pictures, especially throughout Jessie’s childhood and beyond. For the most part, at a certain point the pictures just stop. Hers is the only baby-picture book that remains painfully incomplete. Of course, Jessie was the fourth child, and our mother’s days were full of tending to three other kids, a herd of various pets, and a husband who came home from interning at Roosevelt Hospital in New York City only on weekends, if then. I treasure any pictures of us that were taken as we were growing up because they shine a light onto memories full of shadows. Without their validity and light—solid evidence surrounded by a solid frame—all is vague and mutable. So I will attempt to reconstruct a few memories of Jessie from images in my mind’s eye that I have carried with me all these years.

Jessie must have been about eighteen months old—a pale baby with patches of wispy blond hair and big blue eyes. I notice the blue veins in her temples. Mom is trying to feed her. For some reason this image is set in a tiny back room of Stone Cottage, our family’s first home. The walls of the room are painted a dark green, as it is our father’s study when he is home. There are shelves stocked with strange-looking medical instruments, including clamps and long, skinny metal tweezers. Could that be true? I don’t remember a desk. Had that room been turned into Jessie’s room?

Jess was always an extremely picky eater. Mom would spend hours trying every baby-seducing trick she could think of in an effort to get her to open her mouth. There is a little rhyme she would use in an attempt to throw Jessie off guard:

Knock, knock! (Mom gently knocks on Jessie’s forehead)

Peep in! (Mom pushes up Jessie’s eyebrow)

Lift the latch! (Mom gently pinches the end of Jessie’s nose)

Walk in! (Jessie’s cue to open her mouth)

Chin-choppa! Chin-choppa! Chin-choppa! (Mom moves Jessie’s chin up and down as if she were chewing)

Every now and then, the enthusiastic coaxing and funny faces would make Jessie laugh, and Mom had to be quick on the draw to get in a spoonful. Sometimes nothing worked, and Mom, exhausted, would have to declare a truce, defeated by the stubborn little person in the high chair. When she got older, Jessie went through a plain-spaghetti phase; later, red licorice seemed to be her sole sustenance. She was always a skinny little thing. She still isn’t that thrilled by food and has never had the desire to cook. When she does, it is usually with less than felicitous results.

Our lives changed after we moved from Stone Cottage to Hermitage Farm, on John Street in Greenwich. Our parents bought the farm from Granny Close after Granddad Close died. Granny herself moved into a tiny cottage next door, over a high stone wall. Our parents were getting more and more involved with Moral Re-Armament, so they weren’t around a lot. Meanwhile, Granny was determined that we get a religious education. Most Sundays we would straggle behind her up the bluestone path into the local Episcopal church, dreading Reverend Bailey’s boring sermons. The church was called St. Barnabas, so we called our Sunday travail the Barnabas and Bailey Circus. There are no images of our mother and father in that scene. Without them it was as if the center of our universe had fallen away and we were solitary planets with no gravitational pull to keep us from spinning away into separate orbits.

We eventually moved into a house on an estate called Dellwood, in northern Westchester. Dellwood had been donated to MRA by one of Vanderbilt’s granddaughters and was used as an MRA center. In my memory Jessie is often nowhere to be seen. What was it about those sad days that my mind refuses to retain? Tina was twelve. I was ten. Sandy was eight, and Jessie was almost five. We weren’t abused. We always had clean clothes and good food and a solid roof over our heads.

I have always felt very solicitous of Jessie. She touched and amused me. She was funny and deeply original and had a wonderfully expressive face. I loved her quirky outlook on life. I used to tease her, knowing that her reactions would be dramatic and funny. Looking back, it seems horribly cruel, but at the time it was just big-sister razzing. Once, we were washing dishes after dinner in the kitchen at Dellwood. There was a window behind the sink. Night had turned the window black. Jessie was drying dishes at my side, my happy helper. Suddenly I stiffened and stared into the darkness outside, widening my eyes and pretending to hyperventilate. Jessie froze. I moaned and then built up to a shout: “Oh, no… oh, no… oh, no-o-o!” Jessie started screaming and stamping her little feet, looking like she was running in place, whipped into hysteria in a split second.

Another time, I put a sheet over my head and slowly peered around the door into Jessie’s bathroom, where her nanny, Meta, was giving her a bath. Jessie was standing up in about three inches of water as the tub filled up. When she saw the ghostly sheet, she started screaming and stomping her feet. Water splashed all over the walls, not to mention all over Meta. I got yelled at, and Jessie eventually calmed down enough for a bedtime story. Needless to say, she was too young to think it was funny.

My most powerful image from that time in our lives: we are in the upstairs hall at Dellwood. I think it is daytime, but there is not much light in the hall. I am about eleven years old, so Jess must have been about five. She is standing in front of me in a summer dress. She has two long, blond, skinny braids that reach to below her waist. She is not looking at me, and yet even though I can’t see into her eyes I can tell that she is upset. With her right thumb and forefinger, she is violently rubbing the soft skin between her left thumb and forefinger. She has worried it for so long that it is red and crusty. Sometimes it bleeds. I can feel her distress. I pull her hands apart to try to make her stop. She pauses for a moment, looks up at me, and then starts rubbing again. I don’t understand why she keeps doing something that must cause her pain.

In my mind the scene has no conclusion. It is simply the two of us wordlessly facing each other in a somber hallway. I am intently focused on what my little sister is doing, not understanding why she is doing it and not being able to stop her. I know that outside there was a garden and a lawn gently sloping down to a shaded, grassy path leading into shimmering hay fields. Maybe our collie, Ben Nevis, was trotting up from those fields at that very minute. Downstairs and out the front door of the house, across the driveway and up a set of stone steps, were a swimming pool and a set of swings. I’m not sure if there was a sandbox, but there was cool sand under the swings. Through the open, shaded windows in the bedrooms that opened into the hallway, we would have been able to hear the metallic, sawing sounds of cicadas in the high heat of the summer day. But all I see in my memory is a silently distraught little girl, my sister, standing alone in front of me, mutely intent on making herself bleed.

CHAPTER FIVE

When I turned seven, our family left the United States and moved to the renovated hotel now called Mountain House in Caux, Switzerland, which MRA had converted into its international headquarters and training center. A photograph of my sisters, brother, and me shows Tina as a slim teenager, a freckle-faced Glenn smiling, Sandy looking very much like a disgruntled adolescent, and me with very long braids; after almost two years in Caux, those appearances would change dramatically.

Although Mountain House has a fairy tale look to it, I found it to be a cold and formidable place. If my memory serves me correctly, I was on the seventh floor, in room 721. It was connected to room 720 by a door, and Mom or whoever was taking care of me stayed there. My siblings were scattered throughout the four-hundred-plus-ro

om hotel. Tina held the record for switching accommodations, moving to thirty-two different rooms during our stay.

I remember the Reverend Buchman lived on the fourth floor, and everyone was told—especially children—to walk quietly and never run on that floor! There were no dogs at Caux and almost nothing fun for me to do. Tina and Sandy got into trouble a lot, although Tina was better at not getting caught. Sandy and his Nigerian friend, Azecaru, recruited me once to throw rocks down onto the little cog railway that came up the mountain from Montreux every day. When the train stopped, we ran, screaming, across the grounds into Mountain House. Thankfully, we weren’t caught. MRA didn’t believe in sparing the rod, although in MRA the “rod” took the form of a lecture.

In Caux, we were all told we needed to “have guidance.” Adults were supposed to have guidance as soon as they woke up each morning. Those most on the ball would be expected to attend the 7:30 a.m. set up and plan for the big 11:00 a.m. meeting. It was held in a massive room that had a grand domed ceiling. Everyone who wasn’t on some work shift was expected to attend, and each meeting began with a chorus singing snappy MRA songs loaded with message. For a child, it was all incredibly boring. And uncomfortable. It was difficult to sit still for that long when you were small. We had to wear dresses; as a result my bare thighs would stick to the metal folding chair and my underpants would bunch up. I would put my head back as far as it would go onto the back of the chair and pretend to be sliding down the slope of the domed ceiling high above me. I would create a whole world up there, above our heads. I have kept my habit of looking up at ceilings and imagining how a room would flow if it were upside down.

We were told to call the Reverend Buchman Uncle Frank: his second in command, Peter Howard, was Uncle Peter. I was convinced, at seven years old, that Uncle Frank was God and Uncle Peter was Jesus.

During the morning meetings, Uncle Frank would sit in an elaborate wooden armchair, always with his cane, on a raised podium covered by Persian rugs. His wire-rimmed glasses connected his huge ears to his long, pointed nose. I tried not to look, but the end of Uncle Frank’s nose, besides usually having a drip poised to drop, resembled a tiny butt, and that was a “dirty thought,” which we weren’t supposed to have and which I certainly didn’t want to have to confess. Every night after saying my bedtime prayers, the woman with me would ask if I had had any dirty thoughts that day. Once, not being able to think of any, I told her I’d been wondering what Uncle Frank looked like without any clothes on. I got into big trouble! I was told that I was bad and that I had a “dirty mind.” Guilt was how we were punished, and it worked well.

Under the strict thumb of the Reverend Buchman, MRA leaders dictated what was and wasn’t permissible behavior—not just for us children but for our parents, too. Any independent thinking was seriously “off the ball” and went against God’s will. MRA’s mantra was “When man listens, God speaks”—and, as in all cults, only the leaders had the ability to discern when God was speaking.

My father later wrote:

When I squeezed my past, including my activities as the squadron morale-and-booze officer during the war, through MRA’s moral wringers, I was pronounced ready to serve… Freed from guilt and energized by self-righteousness, we sacrificed our personal ambitions and sexual drives to a noble cause… We committed our lives to God, to MRA, and to living by the Four Absolute Standards.

My parents’ decision to dedicate their lives to the Four Absolute Standards meant that we had to follow them, too. Adults who were “freed from guilt” put guilt into their children as a matter of course and as a method of control.

What I remember most about living in Caux is being isolated and lonely. I hardly saw my siblings. I missed Hermitage Farm and would have preferred living in Dellwood. At least my siblings and I would have been together.

With my parents gone, the job of rearing me fell mostly to Meta. Each morning when I got up, I took out the notebook she had given me and tried to think about God and what he wanted me to write. I had been told to focus on my sins and carefully record all of them so I could share them with everyone at the 11:00 a.m. meeting. I really couldn’t think of any sins—I was only seven—so I wrote down what I had heard another girl say the day before, and then I got dressed.

Each of us had chores to do. Mine was helping clear the tables in the hotel’s dining room. The plastic trays were heavy, so I had to be careful when I carried empty glasses and dirty plates so I wouldn’t drop them.

After chores, I walked to our MRA school, which was about a ten-minute walk from the hotel, inside a two-story house called Chalet de la Forêt. It was where all the younger children attended school, which was taught by MRA teachers. There were about fifteen of us—sometimes more when new families arrived at the hotel. Although I didn’t see Tina and Glenn, I knew both of them were day girls at St. George’s School outside Lausanne. I wasn’t sure where Sandy was being taught.

The teachers taught us to sing and on special occasions asked us to dress in our national costumes. Because I was from the United States, my national costume was my everyday clothes. I was jealous of the girls from Holland and Germany, who got to wear fancy dresses, while the boys wore lederhosen. Jealousy was a sin, so I didn’t tell anyone, but I craved the other girls’ outfits.

The Reverend Frank Buchman was in his eighties in 1960 and nearly blind, but he liked to be onstage and wanted us children to sing whenever a big group came to visit. On our birthdays, we would receive a present from him—it was always a handkerchief embroidered with either a Swiss chalet or a Swiss man blowing one of those long horns—and our teachers would help us write Uncle Frank a thank you note or send him a drawing that we’d made.

I wrote him a thank you note that was later reprinted in a book published by MRA.

Dear Uncle Frank

Thank you very much for the handkerchief.

There are lots of cows around the chalet where we are.

Two roosters are always calling to each other.

Every day we go for long walks.

In the morning the cowbells and the roosters wake me up. I hope you have gotten more strength because that is wot I have been praying for.

Sincerely,

Jessie Close

I would wonder years later how I could spell handkerchief correctly but misspell what. I decided all of us learned the word handkerchief rather early, because that is what the Reverend Buchman gave everyone on their birthdays.

Glenn would later tell me that she met Uncle Frank in the “inner sanctum,” where he lived. He told her that a drawing she’d given him was “priceless.” As soon as she was escorted from his room, Glenn began crying. She thought “priceless” meant that her drawing wasn’t worth anything.

Each of us would grow up with different memories of the two years that we spent in Caux. As an adult, Sandy would recall bitterly how he had been taken into a room with other preteen boys by an MRA leader who demanded to know how many times they masturbated every day and then pressed them for details about what excited them—all under the guise of helping them overcome their sins. Tina would remember how she was put to work in the hotel’s main kitchen. It was exhausting, but she was a hard worker and would be moved up the ranks. Eventually she would become a server in the Reverend Buchman’s private dining room, but she would only last a week there before she would get caught flirting with one of the boy servers and sent back to the kitchen as punishment.

One of my most terrifying memories is of the black iron fence that edged the MRA compound. An MRA leader warned me to stay inside the fence, otherwise a “Communist” would grab me. I wasn’t certain what a Communist was, but I sure didn’t want to risk getting kidnapped by one.

In addition to my thank you note to Uncle Frank, the commemorative book that MRA published printed black-and-white photos of other children and me. In it, my hair is cut in a functional pageboy. I am wearing a bulky coat. I look lost. The book’s authors explained in the text that “this was a period w

hen separating children from their parents in [service of] what was perceived as the greater good was sanctioned… [because the parents] were needed elsewhere, doing work which would create a safer and more peaceful world for their children.”

That sounds so noble when you read it, but it wasn’t really. Even today, Tina’s eyes fill with tears and her voice chokes with emotion when she recalls living in Caux. She felt completely abandoned by our parents. We all did.

If any of us complained as children about being separated from our parents, MRA grown-ups would make us feel guilty by telling us that we were selfish. How dare we put our own desires above the good that our parents were doing? I remember writing a letter to Jesus thanking him for taking my parents away from me to do good in the world. Many years later, a therapist asked me if I understood how unnatural that thank you letter was. Parents were supposed to protect, not leave. I was in my thirties at the time and really hadn’t thought of my parents’ leaving as being unnatural.

Because I rarely saw either of my parents, I didn’t know what their great mission was. I would learn about it later, largely from reading my father’s autobiography. It’s strange reading about your father’s life during a period when you were little and wanted to be part of it but were left behind.

In April of 1960, my father was one of five men and one woman selected by MRA to become missionaries in what then was known as the Belgian Congo. My dad wasn’t chosen because he was a medical doctor. They wanted him because he spoke French, which was the country’s official language. My mother was not assigned by MRA to go with him.

“I guess I’ll take my black bag along,” my father told her when he was packing to leave Caux. “You never know; it might come in handy.”

Resilience

Resilience